A mother in her 20s has recurring thoughts about physically harming her child. These thoughts don't make sense to her. She loves her child very much, and the thought of deliberately hurting him is very upsetting to her, like any parent. She decides to take a shower while her baby is sleeping. The shower has the desired effect of clearing her of disturbing thoughts. Gradually, her thoughts turn to more mundane things.

But soon after she finishes showering, thoughts of harming the baby return, and they continue to do so day after day. She becomes obsessed with the possibility that she might actually harm her child. Could she really do what she imagines? The only time she is free from these terrible thoughts is in the shower. Every day she spends more and more time in the shower, trying to wash away her terrible thoughts. Soon she feels like she has to shower again to feel normal. She sees no other way.

In the end, things get so bad that she seeks medical attention. She was diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and offered a combination of medications with psychotherapy. None of these treatments proved effective, so she was referred to the Amsterdam University Medical Center and to our team of psychiatrists.

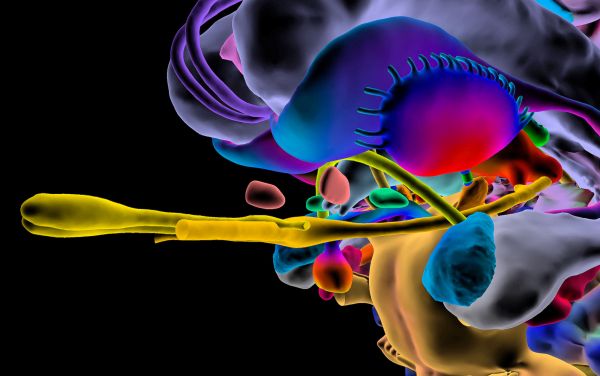

Our group specializes in deep brain stimulation (DBS), an innovative psychiatric treatment offered to a small but significant number of patients who do not respond to psychotherapy or medication. DBS involves implanting electrodes that deliver pulses of electrical stimulation to areas deep within the brain.

We tell our new patient that DBS should have a significant chance of success where other treatments have failed, and she decides to give it a try. First, a team of neurosurgeons implants two electrodes deep into her brain. She has two weeks to recover from the operation. A team of psychiatrists then takes the stage, using a remote control device to adjust the frequency, duration, and amplitude of the current from the electrodes to optimize stimulation. Think of it as a kind of pacemaker for the brain.

Nothing changes at first, and our patient worries that she might be what we call a "non-responder." Then we adjust the stimulation again, and she experiences something that literally amazes her.

Up to this point, she has only felt a deep anxiety that she struggled with every day, but after a moment, she begins to feel good about her life. Restrictions are lifted in seconds. She feels lighter, less burdened by her fear and anxiety. Her breathing slows down and she feels more relaxed. Whereas previously she felt totally dependent on psychiatrists, she now feels able to treat them as her equals. She is happy and hopeful for her future.

Since 2005, our research team has treated 85 patients with OCD. As seasoned philosophers on the team, our interest naturally arose from the instantaneous changes in life experience we observed in these patients. But we are also puzzled: how could the application of an electrical current to neuronal cells deep in the brain lead to such complex changes in the patient's experience as those we have just described? Why do electrical shock-induced changes in the brain have a direct impact on the suffering of patients for whom all other psychiatric treatments have failed? If anxiety can be suppressed in a fraction of a second by simply changing the electrical activity of neurons, what does that tell us about the mind and its connection to the brain? In order to learn more about how DBS has changed the lives of the patients we treat for OCD, we decided to interview a group of them, identifying responses that most accurately reflect these patients' personal stories of struggle and transformation. after DBS treatment. They told us that after DBS they became more confident in their relationship with the world. They trusted their ability to interact with the world. Several patients have told us that they felt energized with DBS:

DBS has definitely done something because now I am much stronger and more powerful. And a lot more, like, you know, that's what I want, and that's what I'm going to strive for, making my own choice. Before, I would never have done this, I didn't dare.

Many patients told us that after being treated with DBS they became more confident and could now be more heard in social interactions:

Well, the mood improves, yes, it becomes more fun - so yes, I began to talk a lot more, became much more assertive, I must say. I really stood up for myself much more, sometimes even too much.

Interestingly, both in our clinical work and in these semi-structured interviews, patients often describe this kind of

and change as a feeling of increased self-confidence. This is interesting because self-confidence is not included in the OCD psychiatric rating scale, and it was not explored in the semi-structured interviews we conducted.

Our patients have experienced an expanded horizon of engagement and interest

Patients told us that they felt that they could again take part in normal daily activities, which they had previously stubbornly avoided due to their fears and anxieties. They were now able to shop for groceries, attend social gatherings, resume their hobbies, and indulge in old interests long abandoned. They dared to do what they had previously avoided. They were more open to possibilities and were able to think and plan for the future again:

So you see all these possibilities and I also started looking into things. And then I think: oh, I can do this, I can build that, and this, in general, is not so difficult ... If it [DBS] did not exist, then I might not have thought do something like that... But now I'm thinking, oh, I can try, and if it doesn't work, it's okay.

Overall, our patients experienced an expanded horizon of engagement and interest. After DBS, they no longer faced a world of threats and obstacles, but were ready to take advantage of the opportunities it offered. Before DBS, the OCD person was rigid and limited, forced to act on his compulsions—all other alternatives seemed closed. They lacked freedom. After DBS, patients tell us they have re-experienced a world of enticing, enticing, and alluring possibilities. For example, the patient may again see the prospect of sailing on his own boat as an attractive opportunity.

There are two sides to the heightened self-confidence we see in our DBS patients, matching themselves and the world. On the side of the world is an expanded range of possibilities with which the patient is now open - actions previously considered impossible. On the side of yourself, new ways of being are now available - for example, the opportunity to become a skipper and sail around Europe. Our patients literally relate to their own existence in a new, more open way, with a greater understanding of who they really are. When one is once again fascinated by the exploration of Europe's waterways, one sees a whole new way of life as far as possible.

In his major work Being and Time (1927), Martin Heidegger used the concept of "projection" (Entwurf) to describe two aspects of self-confidence that we distinguished in DBS patients. In ordinary German, the noun Entwurf and the verb entwerfen refer to a sketch of some project to be done (for example, an architect drawing a new building in a sketchbook). Heidegger points out that designing is not thinking about and implementing a plan. Instead, it refers to the freedom that a person must push forward in a range of possibilities; it means taking a stand on who we are. With the help of Entwurf, Heidegger hoped to capture the driving force of life.

People can seize opportunities and embark on projects that shape their self-understanding—people's understanding of who they are. For Heidegger, a person's self-understanding of who he is comes from openness to the world and its possibilities. However, for a person with OCD, the world is permeated with an atmosphere of compulsiveness. Therefore, the openness of this person to the world is reduced to the possibilities that he considers necessary to use. Before the treatment, a young mother who came to our clinic felt that she had no other choice but to take a shower, even for a temporary sense of normalcy. The range of possibilities she saw was severely limited by her anxiety. This meant that her opportunities in life were also limited. After DBS, the range of attractive opportunities she saw expanded, and with it, her self-understanding and self-confidence, much like a flower bud opening when its time had come. Her increased openness to the world has allowed her to grow and flourish as a person again.

The growth of self-confidence brings the patient to a point where he can begin to respond to psychotherapy.

The increase in self-confidence that a patient experiences with DBS can be understood using Heidegger's concept of projection—the ability to move forward in a range of possibilities that promotes self-understanding. Heidegger believed that caring for such opportunities is the essence of man, but OCD interferes. The self-understanding of a person with OCD is severely hampered by their inability to move forward towards attractive opportunities that matter to them. DBS helps restore the ability to shape yourself with your actions.

Why does electrical stimulation of the brain restore the ability to predict a possible future that is not caused by the patient's illness? Direct effect on fu

brain function and neural mechanisms can provide the answer. Patients treated in our hospital, for example, receive stimulation of brain regions located in the ventral striatum, which leads to changes in the large-scale connections that form between the striatum, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala, brain regions that play a role. in decision making, memory and thinking. It can be hypothesized that the transformation after DBS can be explained by changes in this once dysfunctional neural network.

But this cannot be an exhaustive answer. The changes a patient experiences after DBS go far beyond reducing their obsessions and compulsions. They include a complete change of a person, including an increase in self-confidence; however, loss of self-confidence is not among the symptoms currently used to diagnose OCD.

The reduction in symptoms that patients experience after DBS is perhaps best seen in the context of the increase in self-confidence and the impact this has on the patient's overall life. For example, several OCD patients in our study noted that their attitude towards their compulsions became completely different after treatment with DBS: they no longer bothered them. Perhaps the increase in self-confidence brings the patient to a point where he may begin to respond to psychotherapy, which may help him make further progress in reducing his obsessions and compulsions.

We have now come full circle in our efforts to unravel the effect of DBS: why exactly is DBS so transformative—not only by eliminating OCD symptoms, but also by increasing self-confidence and openness to the world? And how can we understand self-confidence in the context of electrically induced brain changes? Perhaps changes in the brain and increased self-confidence are necessary to cure a sick person. Thus, understanding the effect of DBS on the brain may be only part of the explanation for how DBS changes a person.

The whole person reacts to DBS, and not just those parts of his brain where the electrodes are implanted. DBS is changing many aspects of how a person interacts with the world. Their social interactions, propensity to think and reflect, mood, interests and, more generally, their self-confidence in life. Even for those without pathology, experiences of overconfidence and underconfidence can be common throughout life. Imagine that you are going to an interview about your dream job. In such a situation, many may experience self-doubt. On the other hand, overconfidence at work can lead to hasty calculations and risks. Excessive self-confidence can develop into impulsive actions that seem pathological; Too little self-confidence can lead to anxiety and a lack of trust in yourself and the world.

Why can self-confidence be critical to recovery from OCD? The answer lies in Heidegger's notion of projection, which can exist on a continuum with ordinary everyday anxiety and insecurity at one end and pathologies such as obsessive-compulsive disorder at the other. Disturbances in projection may be a risk factor for psychiatric illnesses that have hitherto been overlooked by psychiatry. Projection can also be a bridge from illness to recovery. Patients with DBS experience an extended horizon of involvement and interest. They feel able to recapture the opportunities that matter to them. Perhaps it is the projection (extended openness of a person to the world) that inspires self-confidence, opening the way from illness to health.

The world of a young mother who came to our clinic has shrunk to the four walls of a house and caring for her child. When OCD took over, her world narrowed even more, as did her self-understanding. Her life was consumed by the rituals she developed to rid herself of tormenting thoughts. Her unwanted thoughts of physically harming her child took on a life of their own. We all experience unwanted, socially unacceptable thoughts from time to time. We may even find ourselves surprised and disturbed by these thoughts. Basically, we somehow avoid getting too carried away with such thoughts. We have a basic trust in ourselves and the world. However, as she developed OCD, the young mother began to doubt herself and what she could do. The habit of taking a shower was her way of compensating for this insecurity.

Most of us would approach El Capitan with fear. Honnold approaches this with a desire to learn and grow.

On the contrary, a self-confident person trusts himself and the world. They are open to the possibilities the world has to offer. Take, for example, Alex Honnold, the master of "free solo climbing": he slowly but surely climbs the biggest cliffs in the world without any ropes, harnesses or safety gear. In 2017, he fulfilled his dream and rose

on El Capitan at 3,000 feet in Yosemite National Park without any support.

The film crew accompanied him through a long period of preparation for the ascent, attempts, failures and, in the end, success. In the follow-up film Free Solo (2018), Honnold reveals that his climbing experience is one of slow, calm, and steady exploration of rock. Most of us would approach El Capitan with fear. Honnold approaches climbing with a desire to learn and grow through the challenge. Through careful preparation, he trained himself to be fearless and tolerant of intense stress caused by life and death situations. A climb that would seem impossible to even the most experienced free solo climber is an opportunity he was able to explore in a playful way and eventually master.

The pursuit of sensationalism, such as free solo climbing, may seem like an unhealthy personality trait to those who do not like risk. Why is Honnold's free solo not an example of extreme impulsiveness and risk taking? His self-confidence is different from the self-confidence of people who enjoy taking risks. For Honnold, the thrill of climbing doesn't seem to involve living on the edge, risking one's life in the process. His calm confidence allows him to explore the possibilities of climbing to his limits. This openness to possibilities allows him to learn and grow in his craft. In short, self-confidence gives him the opportunity to realize his potential as a climber, to succeed in the cause to which he devoted his life.

Honnold's story offers an important clue as to why self-confidence may be important for a person's mental health. Self-confidence can be understood as a person's openness to the world and the opportunities it offers. As long as a person has OCD, they will remain closed to the world. They will doubt themselves and the world, while others will feel carefree and move forward. Their response to this doubt is to retreat from the world into carefully orchestrated rituals that allow them to manage their insecurities. Honnold also learned to manage his stress and fears. However, he is different from people living with OCD in that he can now use his high stress tolerance to explore the very edges of what is possible in the world of free solo climbing. Self-confidence can open the door to mental health because a confident person is open to the world and its possibilities.